Iroquois Middle School - The Genius Year

When you walk into my middle school English classroom at Iroquois Middle School in suburban Niskayuna, there is a chance you’ll see groups of students discussing a piece of literature or working to peer review each other’s writing, but there is an even better chance that you will walk in to see 25 students working on 25 different assignments for one of close to a dozen different courses.

As I near the end of my second decade as a middle school English teacher, I have come to the conclusion that the skill development that occurs in my course happens in much the same way that students develop skills in a physical education course. We introduce a skill to my team of 125 students, there is guided practice, then they play. Students have the opportunity to develop and demonstrate writing and reading skills just like they would demonstrate running and jumping skills to a physical education teacher. A physical education teacher can assess a student's ability to run through dozens of activities, and as an English teacher, I can do the same with student reading, writing, listening and speaking skills. Furthermore, I have concluded that my students are just as able to design activities that highlight their strengths as I am.

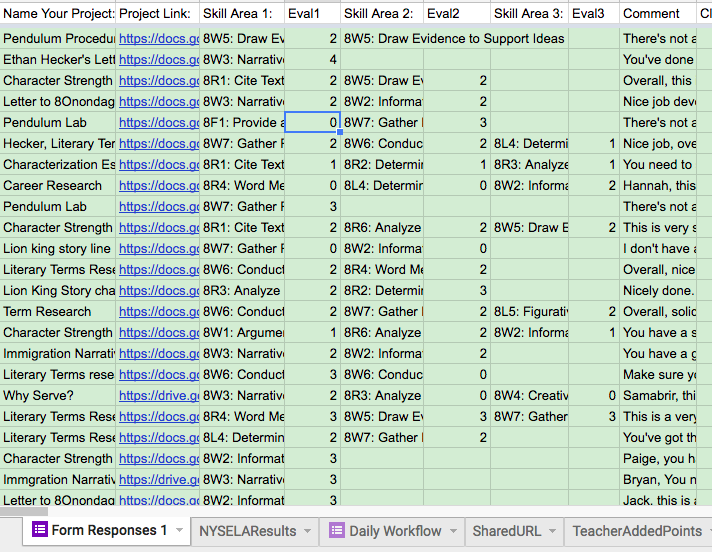

When students enter my classroom, they are asked to consider what types of projects they might complete to demonstrate that they are developing in many different English skill areas. They examine learning standards (C.C.L.S., ISTE, etc.) just like they would other dense, non-fiction texts, and they make decisions about how to demonstrate that they are growing and learning. Sometimes, skills are presented in conventional ways, through a paper, or a book review (see example, below), or a vocabulary study. Eventually, those skills are demonstrated through projects that students choose, and often those projects are the same assignments that are submitted to teachers of other courses. I regularly read student writing that has been assigned by a social studies, science, health, or technology teacher. There is no limit to the type of project a student can turn in for English credit.

The Feedback

The Game

There is also a strand of gamification that runs throughout this English course. Instead of earning a percentage grade for each project, students earn points. Students start the year with zero points, and they gain points towards a final grade for each quarter. This works in exactly the same way that players earn points in video games. A student who does nothing gains no points, and a student who consistently turns in work earns lots of points in lots of ways.

Level Up!

It has become clear that it is possible to “hack” student perceptions about grades. In my course, I have easily substituted percentages for points (which is no revelation), but I have also replaced the value of a “quarter grade” with the idea of the “Level Up.”

The program that we have built allows students to accrue a “Total XP” score throughout the year. Each time a new point level is reached, the student feedback page changes levels. These levels are all derived from fictional worlds (Hogwarts, Middle Earth, Narnia, etc). Within these new levels, I have hidden “Easter Eggs” that are almost always small projects, or side-missions, for students to complete for additional English credit. I have derived each of these Easter Eggs to align closely with a single learning standard or skill. Students think they are earning secret points… I know they are demonstrating English skill through a series of hidden mini-assignments or lessons.

Autonomy and Agency

The current state of technology has allowed teachers to connect with individual students on a daily basis, using detailed information to help promote growth. By extending the “Genius Hour” to the “Genius Year,” I have started to unlock the reality that each of my students can play an integral role in developing an English curriculum for themselves that will help them to grow significantly throughout their year in my middle school classroom.

Works Cited

- Barlow, Emma. “Photograph of a father hugging his son.” Female First, 15 Sep. 2015.

- OffensiveArtist. “Photograph of the Realm of Middle Earth.” 16 April 2017. Wikipedia.

- Wikimedia. “Harry Potter and the Cursed Child Special Rehearsal Edition Book Cover.” Wikimedia.